One of the reasons I enjoy shooting at night is because you never know what you (or the camera) might witness, occurrences that may be mundane, but sometimes things or phenomena that give insight to the physical world around us. Lots of talk the last few years of Starlink satellites and how they are ruining the night sky, yet as a night photographer I have a bit of a different perspective, despite my acknowledging that there are indeed many more satellites in LEO (low earth orbit) than there used to be. My suggestion would be to ignore all the clickbait headlines about satellites ruining the night sky and the FAA recently ‘grounding’ SpaceX’s Starship (it will fly again, once the launch facilities are appropriately updated; whether it ever gets to Mars is a different matter).

Starlink Satellite Brightness Issue

SpaceX has done much to mitigate the brightness of their Starlink satellite constellation ever since the very first launch of the v0.9 test units back on May 23, 2019 (as an aside, I happened to witness those satellites being released from Dragon’s stage 2 module, back before anyone had seen such a thing; by the time my tripod was set up, they were just fading into the earth’s shadow). I shoot a lot at night, and you can mostly see Starlink satellites right after launch as they release in a ‘train’-like arrangement (many of us have seen this now) and subsequently raise their orbits, as well as around twilight when the sun is still relatively close (beneath) the horizon. Once true night sets in less than 2 hours later their ~540km orbit altitudes keeps them mostly in the earth’s shadow, making them practically invisible to most casual observers (astronomers with large telescopes admittedly have some issues capturing data, but often the effects can be mitigated through processing).

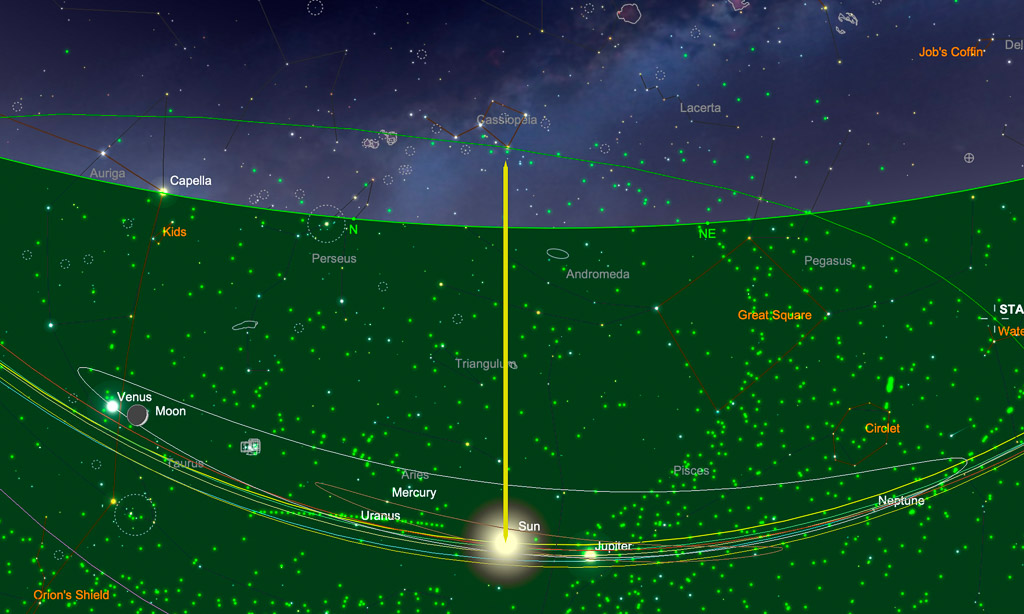

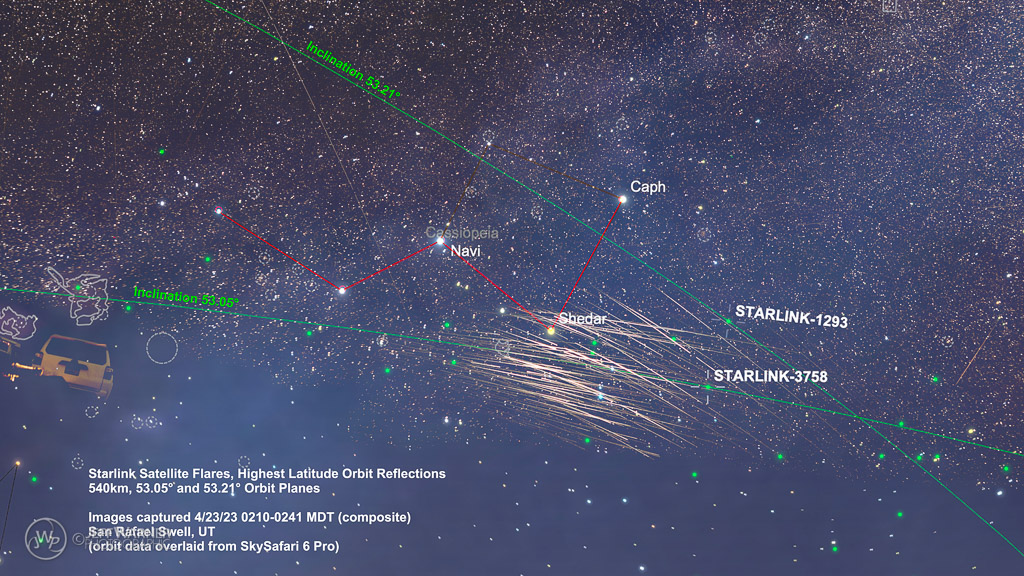

My point in the opening paragraph is illustrated by how few other satellites you see in the first image above, a time-lapse composite that spans a full 30 minutes 13 seconds; there are perhaps 7 ‘other’ visible satellite passes in that timeframe, compared to the 60+ that are shown flaring. I could easily see the flaring satellites at the time, all the rest were too dim for my poor human night vision to see. Perhaps the nocturnal animals are freaked out by all the new satellites in the sky, but most humans can’t see them except in the most favorable conditions.

Starlink Satellite Flares

Those of us interested in the night sky may remember Iridium flares, which could nearly be seen in daytime if you knew where to look (there are applications that list these flares in advance, for a given location). This type of flare can occur when you are located in a small area where you can briefly see the sun’s reflection off the solar panels of the satellites, and they were very brief, periodic occurrences for the Iridium constellation. They have since reached end-of-life and have been mostly de-orbited, but you can witness the phenomenon with other existing satellites in the night sky, though they are more random occurrences (often tumbling space junk, etc.); most satellites don’t flare often during normal operation.

That being said, it is not well-known that Starlink satellites do, in fact, flare, though only in a very specific instance. I happened to witness this late last night while photographing the Lyrids meteor shower in southern Utah, so turned the camera toward the north to capture a sequence. Most Starlink satellites launch from Kennedy Space Center in FL, and the maximum orbital inclination that can be attained at that location is 57°. What we see in the images are Starlink satellites that are at their maximum longitude (53°, the most northerly point of their orbits), and are directly above the sun, revealing a brief illumination as they pass. I do not believe that any applications that track satellite visibility track these types of flares as they occur so close to the horizon (often below) and are difficult to observe, often seen mostly by pilots of high-altitude aircraft (I assume that there are some associated ‘UFO’ reports as a result).

Lastly, the images compiled into a time-lapse; note how you can see that the brightest part of each flare moves to the right (east) as the earth rotates: