Every once in awhile you’re out shooting and you capture something unusual. One of the primary reasons I enjoy capturing images of the night sky is because I never really know what the result will be, as the conditions of the night sky are as ephemeral as our weather, and many different phenomena can affect the images. This July new moon cycle I spent in the mountains of Colorado, mostly in the San Isabel National Forest. My last night out I decided to image from the top of Independence Pass at 12,095’ MSL. The previous nights’ skies had been quite clear, and it was my first opportunity to use a highly-regarded-for-astro lens, the Sigma Art 35/1.4. Observing the sky that night with a pair of rather average binoculars, I was able to see very small stars in dim fields of view that showed as bright pinpoints of light, unlike I’ve seen in the past. Through the (shaky) binoculars I could make out the rings of Saturn, which was a few days out from opposition (its closest approach to Earth). The transparency and astronomical ‘seeing’ of the sky was notably excellent, and I was located in a Bortle Class 2 dark site.

Once astronomical twilight ended at 2036 hrs I started capturing the 9-column by 3-row panorama that I’d planned out in daylight, which took about 45 minutes. The entire time a thunderstorm off in the distance to the northeast had been firing off lightning 5-10 times per minute on average, but I could only see the tops of the cell due to the 13-14k mountains all around me and the lightning was embedded within it, at least from my perspective. It was very hard to determine distance (no thunder could be heard), though I guessed it was somewhere near the Front Range, not in my vicinity, to be sure. Every once in awhile a flash would illuminate nearly my entire field of vision, and this was about 90° off my left, not in my central vision. I’ve watched and photographed a lot of lightning in my day, and the nature of this particular thunderstorm was striking (no pun intended), as the occasional blue-ish flashes seemed to illuminate the entire sky field, not just the actual vicinity of the thunderstorm. Additionally, there seemed to be some structure in the sky apparent to the naked eye; this is sometimes very diffuse cirrus clouds (moisture high in the atmosphere), but from dark sky sites it is often airglow.

Once I finished the capture of the primary pano I was after, I decided to use the camera time to image the thunderstorm, as I felt there was something very odd about it, and it was moving very little. As soon as I took the first test image to determine exposure, it became obvious that the structure I was seeing in the sky was indeed airglow, and of an unusual variety (it looked like colorful ’tendrils’). Typically airglow is red to green, and is caused by the excitation of molecules in the upper atmosphere, kind of an analog to a neon light, and often emitting the same color light as aurora, though from a different process. The airglow on this night exhibited purple, red, orange, near-yellow to green colors, all in alternating bands!

After moving my Helinox chair and F-Stop Shinn camera backpack out of this new northeasterly view, at 2325 hrs I started a time-lapse sequence (see bottom of this post) of 15-second exposures, and finally had a seat to observe. Although what I saw was pretty stunning (especially considering I could mostly see only the cloud tops), I couldn’t review the images until I got back to our new T@b400 travel trailer (the new mobile office!), after I captured a few vertical panos of the nearly-vertical Milky Way that was now high overhead.

‘Rainbow’ Airglow and ‘Blue Starter’ over Independence Pass, Colorado:

Wow.

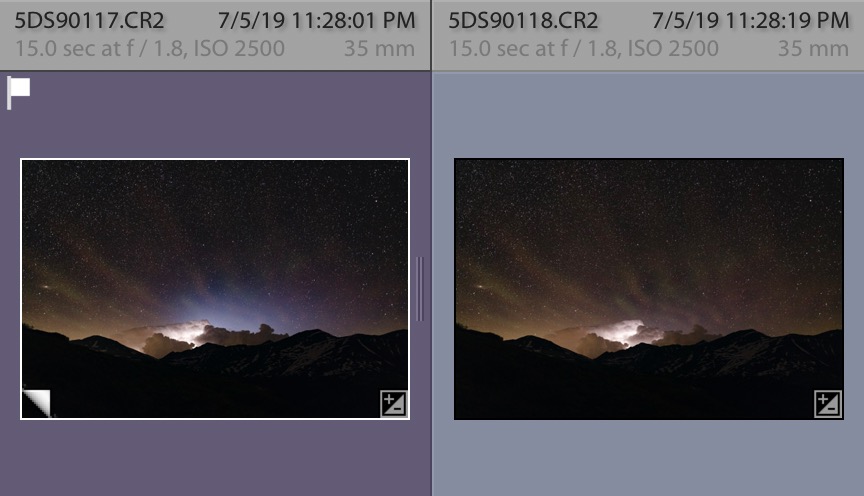

I’d never seen lightning quite like this before, even after 7 years of flying air medical helicopters around the Colorado high country. The unusually bright flashes that I’d witnessed were a fairly bright blue color in the images, and were very unlike all the other images that had captured ‘typical’ lightning on this night; the brightness of even the edges of these images were notably brighter than the ‘typical’ lightning images. The airglow in this sky was also phenomenally beautiful once the contrast in the raw files was adjusted to bring out the detail. No saturation nor localized adjustments were made in any of the sky photographs presented.

In case it’s unclear as to how unusual this ‘blue dome’ of light is, here are two consecutive image captures, one with a ‘blue starter’, one with regular lightning:

[As a quick side-note in case there are any astrophotographers reading, I always process my Milky Way/night sky images using a daylight white balance (color temperature of ~5100-5350K, the ’sunlight’ setting), as this renders relatively accurate colors of the night sky and preserves star colors. Even though many people perceive the night sky to be blue, it is blue for only a short period after sunset, or with the moon up (due to Rayleigh scattering, same as the daytime sky). One of the primary reasons I’ve chosen to do this is so that I can see changes in the characteristics of the night sky from season to season, location to location, from night to night. This is my personal choice, though I’ve seen ample Milky Way images that were quite beautiful using significantly different white balance settings (the predominant color of the Milky Way–and night sky, as a whole–is a sort of amber color). I’ve never taken a yellow/orange sunset picture and changed it to blue, and I don’t think I’ll ever do so for Milky Way images, even though many might prefer it. I digress.]

Anyway, as imaging both here on earth and on the International Space Station has gotten better over the last two decades or so, many of us have heard about odd types of lightning that shoot up into the sky, the most common of which are ‘red sprites’, while the less-common ‘blue jets’ were first documented only back in 1994. These transient luminous events (TLEs) are not common and I’d never captured them before, nor did what I observe resemble the images I’d seen, as both jets and sprites tend to be columns that trend vertically toward the upper atmosphere. What I observed, however, was more a blue ‘dome’ of light that shot straight upward and outward out of the cloud, the light from which was pervasive across my entire my field of vision.

I had no idea what it was that I’d captured, as I’d never seen any images of something like this before. Once I got home I started researching what the phenomenon could be, and even though I thought it had to be some form of blue jet, I could not quickly confirm it, nor could I find any images on the internet of ground-based photographers having captured something similar. What I did find, however, is several images captured from the ISS which exhibited the same sort of blue ‘domed’ appearance over thunderstorms, and these were often associated with red sprites (which there seem to be many ground-based images of). I compiled the 128 images (spanning 39 minutes) into a time-lapse video to try to visualize what was going on within this active cell, which at the time I did not know the location of (I quickly found out that it is hard to find historical radar data, even though you’d think that in this day and age it would be a ‘thing’ to catalog it and make available).

After finally getting some sleep (I’d averaged about 4 hours per night due to the good shooting conditions), on July 8 I finally confirmed the phenomenon, which is a form of blue jet called a ‘blue starter’, assumed to be the precursor to blue jets that never quite break into the upper atmosphere as a ‘column’ (lacking enough energy, I assume). I also confirmed the approximate location of the cell, which was somewhere over/beyond Fort Collins, at least 130 miles away! Cloud tops of this cell had earlier been reported at 55,000’ feet, and there were ample hail reports, mostly up to 1.5” in diameter.

Little is known about these TLE events, but they are assumed to be a sort of analog to lightning with an electromagnetic component–a sort of ‘lightning-in-reverse’–that is, atmospheric charges being built up between our atmosphere and the ionosphere, leading to a discharge. These events are often correlated to hail-producing thunderstorms, but they appear to be somewhat rare, at least from a ground-based perspective. This may be proven wrong in the future, as there is little data nor scientific research currently underway.

Lastly, a quick note about the unusual airglow. Airglow is commonly present in the Milky Way imaging I’ve done from dark sites like central Utah and some parts of the Colorado mountains, but it is typically green and/or magenta. There are a few images of this rainbow-like airglow around the internet, but it also appears to be somewhat uncommon, and I’d guess that the atmospheric conditions that precipitated the blue starters also had a direct effect upon the nature of the airglow, which also dissipated as the thunderstorm activity dissipated. Note that in the time-lapse video the symmetry of the airglow ‘tendrils’ seems to be associated with the location of the the thunderstorm cell, and especially from the part of it from which the blue starters were emanating. I did find some anecdotal info on ‘convectively-generated’ airglow, but nothing formal enough to mention.

Below is an additional image (a vertical panorama, 1 column of 4 horizontal images stacked vertically, which would print natively at 25×40”), as well as a time-lapse video to illustrate what I’ve described above, showing:

- The thunderstorm cell sitting far behind Mt. Champion, at center (13,646’ MSL, 3.2 miles to northeast);

- Light pollution from the Front Range (yellow color near the horizon);

- Vehicle headlights on State Hwy 82 (Independence Pass Road);

- Airglow;

- The disc of the Andromeda Galaxy (at lower left), and

- The ‘northern’ portion of the Milky Way, high above.

‘Rainbow’ Airglow and Blue Starter over Independence Pass, Colorado (vertical):

PHOTOGRAPHIC INFO:

- Canon 5Ds

- Sigma Art 35/1.4 DG HSM

- 15 seconds (60 seconds for foreground)

- f/1.8

- ISO 2500

- Color Temp 5150°K

- Only contrast, slight ’dehaze’, and black point were adjusted during post-processing to reveal detail in the raw files

- Lens profile applied in Lightroom Classic

- In some images I composited a longer (60-sec) exposure using Photoshop CC for the foreground, rather than just retain the black silhouette of the mountains

WEATHER INFO (what little I could find):

- Thunderstorm cell had cloud tops up to 55,000’ at 2130 hrs

- 1.5” hail widely reported in Fort Collins vicinity

- Temp 79°, humidity was ~50% (quite high for CO in summer)

- Jet Stream may have been overhead (unusual for this time of year)

ATMOSPHERIC/SEEING INFO:

- Bortle Class 2 location

- Transparency appeared very, very good

- Little airglow near Milky Way

- Airglow (possibly convectively-generated) above thunderstorm

Unfortunately I had no cell signal to try and gather real-time information from the internet as this was occurring, and thus had no access to many of the common weather/data tools used by astrophotographers.

Look up, you never know what you might see…

Timelapse video of ‘Rainbow’ Airglow and Blue Starters over Independence Pass, Colorado:

One last image of the night’s Milky Way from Independence Pass, with some of the terrain being lit by the setting crescent moon. The valley below is Mountain Boy Basin, while the flank of Mt. Elbert is on the left, La Plata Peak being on center horizon (lights in valley are from a car on the pass below):

Pingback: 6/22/23: Airglow and Gravity Waves from Ridgway, CO - CatchingTime